Apocalypse Now

G L Gilbert envisions a superyachting dystopia within which the industry has collapsed through its failure to encourage and nurture the artisans on which it relied so heavily. Is there still time to change this fateful course?

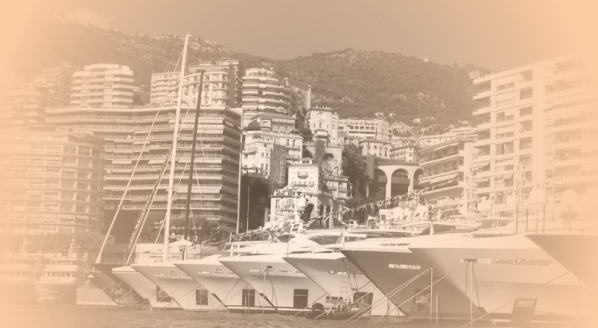

Monaco was a sunny place with sunny people. The shadows in which the wealthy, the indolent and the ne’er-dowells had once hidden disappeared with the establishment of the Sixth French Republic, which crashed like a wave on to the world’s breakwater shortly after what was left of the European Union fell into disrepair in 2053. Luca, looking older than his 70 years, his unruly grey hair buffeted by the wind, stood almost alone on the harbour wall. Gaunt and tall, his slight frame was wrapped against the evening wind by his late father’s navyblue, shawl-collared cardigan that had two buttons missing. He wore his regular, shabby stone-coloured chinos and the salt-spattered Sperry Docksiders that had been with him through the better days; days that had been at sea when Luca served as Master on any number of the great behemoths that once populated the harbour at Monte Carlo.

The Maltese Falcon, the grandest and last surviving of all the sailing superyachts, loosened her moorings and, alone in an empty bay, her sleek black hull silently glided out of Port Hercule as she had done countless times before. Luca had been on board the Falcon many times and would have loved to have sailed her, but it took a special captain to command such a vessel. Many of her successors, and pretenders to her title, had long passed on and found fresh purpose, recycled into the cans of baked beans that lined the supermarket shelves, feeding the descendants of the artisans that had once built them. La Ciotat and Viareggio had become the graveyards of the dreams that typified the Age of the Billionaire, an age unsustainable, unloved, unmissed. Although Viareggio still had an enclave of artisans building yachts, it was far removed from its prowess of those halcyon days.

Luca looked back across the harbour at what was once the Monaco Yacht Club. Foster’s architecture, a last-daysof-Rome tribute to the excesses of the early 21st century, fashioned after a sailing ship by the quayside, had since become a municipal sailing club open to all with the passion and inclination. The building had not changed much, but its days of privilege had gone, together with the great superyachts that had typified its opening.

This latter half of the 21st century was different – more democratic, more egalitarian; the fruits of excess had been replaced by the passions of the many – the yacht club was now all about the sailing. Sat on the harbour wall near where Luca stood were four young teenage boys, indistinguishable from each other in their charcoal-grey shorts and burgundy hooded sweatshirts. All of them were keen young sailors; they dangled their sneaker-shorn feet over the seawall, blissfully unaware of the years that had passed. None of these boys were millionaires, nor were their parents. Yachting had changed and the big vessels had gone. Luca turned to the group of boys and, catching the eye of the keenest and sharpest of the quartet, he said in reflective tone:

“You wouldn’t believe it if I told you that each September, gathered in this place were hundreds of yachts, 40 metres, 50 metres, 70 metres sometimes more than 100 metres in length. They were gilded beyond belief, the distillation of the design dreams of the wealthy who were passionate for the sea and status. Today, you can sit here for weeks on end and never see a superyacht, but in those days you couldn’t throw a stone along the coastline of the Côte d’Azur without hitting a superyacht. There were parts of Italy, Viareggio as I recall, and also Holland and Germany, where tens of thousands would craft and build huge private ships that would make merry with the sea and the wind. Such monuments to man’s command of the sea you could never imagine, the next more monumental than the last, until they had all exhausted themselves and could build no more. Of course, there are still little pockets of yacht building, building smaller more po-lit-ically” – he sounded every syllable as if to make his point – “acceptable, more ecological ways to enjoy the sea. But what great days those were. We may not see their like again for a hundred years – or maybe not at all. If I could go back in time, could we have changed anything?”

Luca turned on his heels and headed to the Quai des Artistes for an early supper – a plate of salt-crusted sea bass with a glass of something white. At least some things never change in Monaco.

NEW: Sign up for SuperyachtNewsweek!

Get the latest weekly news, in-depth reports, intelligence, and strategic insights, delivered directly from The Superyacht Group's editors and market analysts.

Stay at the forefront of the superyacht industry with SuperyachtNewsweek

Click here to become part of The Superyacht Group community, and join us in our mission to make this industry accessible to all, and prosperous for the long-term. We are offering access to the superyacht industry’s most comprehensive and longstanding archive of business-critical information, as well as a comprehensive, real-time superyacht fleet database, for just £10 per month, because we are One Industry with One Mission. Sign up here.

Related news

The final curtain...

The sun sets on Donald McLaren’s journey with The Superyacht Group... Or does it?

Owner

Dreams for sale

In the latest excerpt from our G L Gilbert serial, Donald receives an interesting offer while at the Monaco Yacht Show

Owner

G L Gilbert: ‘God bless her’

We revisit the travails of Donald McLaren for a little lighter weekend reading, ahead of the publication of new material next week

Owner

Related news

The final curtain...

7 years ago

Dreams for sale

7 years ago

G L Gilbert: ‘God bless her’

7 years ago

NEW: Sign up for

SuperyachtNewsweek!

Get the latest weekly news, in-depth reports, intelligence, and strategic insights, delivered directly from The Superyacht Group's editors and market analysts.

Stay at the forefront of the superyacht industry with SuperyachtNewsweek