The final frontier: a neo-Homeric odyssey

He’s been to space and summited Everest. But Victor Vescovo’s magnum opus might be unfolding in the uncharted darkness of the deep…

Victor Vescovo. Image © Tamara Stubbs

As I sit with Victor Vescovo in a nondescript hotel café in West London, it’s hard not to become platonically enamoured by his candour. He doesn’t speak like someone who has been to the deepest depths of the world, or even someone who has gone beyond the stratosphere, although the latter is particularly refreshing given the famously dry demeanour of some astronauts.

Despite building his wealth through private equity investing and having previously served in the US Navy for two decades, there’s no trace of a billionaire’s bravado; rather, a plainly passionate speaker and adventurer, as we discuss submarines, satellites and shipyards.

This is from a man who’s summited Everest, skied to both poles, plunged to the deepest point of each of the five oceans, touched the corner of the cosmos and even invested in the company that recently resurrected dire wolves. His CV reads more like Bruce Wayne’s bucket list, but the man himself is more engineer than ego, more mission than mystique. And his latest project might be his most mammoth undertaking yet. For now, at least.

As some magnates race each other into space, it is what lies beneath the surface of our world that commands the Texan’s attention once more, looking toward the yawning voids of the Earth’s oceans – the final frontier we have somehow skipped.

“We’ve mapped the surface of Mars and the Moon in detail. We’re sending billion-dollar probes to the outer planets,” he says. “But why? We still use some navigation charts today that are based on Captain Cook’s measurements from the 1700s. We’ve missed almost two-thirds of our own planet.”

Within Vescovo’s crosshairs is the hope that he will set a new standard for deep-sea exploration by building an AI-enhanced 23-metre mapping vessel, the aptly named Ocean Mapper. With hull model testing now complete in Norway, the team is now entering the shipyard bidding phase, with interest peaking from varied corners of the maritime sector.

Ocean Mapper rendering

Penned in Monaco by design stalwart Espen Øino and hydrodynamic and shipbuilding specialists Engineering IDS, Ocean Mapper is built to the core tenets of efficient, semi-automated exploration . The boat is set to be crewed by two (yes, two), with the potential of solo manning still a real possibility. And of course, Vescovo has already vowed to take to the helm first as proof of concept.

“Over the past six months, we’ve spent the time and the money to build two ship models and test the sonar gondola in a tank. The goal was to ensure the acoustic return wouldn’t be disrupted by bow bubbles, so we designed a specialised axe-shaped bow,” he explains enthusiastically.

“The entire ship is completely optimised for sonar performance and long-range ocean cruising with a 7,000-mile range. Espen and IDS really understood the mission and the engineers were excited. They told us, ‘No one’s ever asked for a ship like this before’. And when you give fantastic engineers like this something meaningful to solve, that’s when they do their best work.

Ocean Mapper rendering

The project’s holy grail is efficiency. Engineered to map the ocean floor at scale for a fraction of the cost of other vessels, the compact vessel’s capabilities allow for deep-sea terrain mapping for as little as $2 per square kilometre to a depth of 4,000 metres in optimal conditions. It’s necessitated a no-nonsense approach too – this vessel has to function as intended, without luxuries or gimmicks. It will run on trusty diesel engines. They’re reliable, fuel-efficient and can even run on biodiesel if needed.

And just in case he fancies hitching another ride to Challenger Deep, the Ocean Mapper can also utilise micro-landers capable of descending to full ocean depth at 10,935 metres. These landers can record bathymetric data, collect water and biological samples and perform in situ component testing in the extreme pressures of the deep ocean.

“Our estimates show it’ll cost about $500,000 to $600,000 a year in fuel to run it 300 days a year. That’s staggeringly low when compared to a ship twice the size. The smaller the vessel, the more efficient it becomes. Believe me, acquisition and operating costs are going to blow people away,” adds Vescovo.

Naturally, sonar quality is imperative to ensuring the data collected is worth its weight. It will carry a Kongsberg EM124, arguably the most powerful sonar one can install on a civilian vessel, and operate at a modest 10 knots, transmitting data via satellite and covering up to 10,000km² per day.

This is by no means Vescovo’s first time in the deep end either. Before this vessel was ever designed, Vescovo had already gained hands-on experience with the technology. “I bought [the Kongsberg EM124] serial number one and helped debug it with my team. We went all over the world and mapped four million square kilometres over four years,” he recalls.

“But from that experience, looking at the cost, the technology, the crew, I was able to go, okay, how could we do this better? Like a businessperson. Because at the end of the day, I’m a technologist, not an ocean researcher. I build this stuff, then let people smarter than me use it.” That journey ultimately led him to sell the system two years ago to the deep-sea research firm Inkfish, allowing him to start again, smarter, cheaper and faster.

More recently, Vescovo and his team have mapped half a million square kilometres of coastal area, including 1200 square kilometres of the British coastline. Using freely available imagery from European satellites, analysts mapped coastal regions shallower than 30 metres. These human-generated datasets are then used to train an AI model to replicate the process faster and at scale.

Continuing the effort to explore the capabilities of satellite-derived bathymetry (SDB) with partners TCarta and Greenwater by donating 1,287 sq km of UK coastal area to Seabed 2030. There might be some overlap, but hoping the UK can continue its efforts to map 100% of its EEZ. pic.twitter.com/EmiBuCikQ1

— Victor Vescovo (@VictorVescovo) June 21, 2025

“What we discovered pretty quickly, however, is that different parts of the world are incredibly different in terms of their hydrography, so training the AI has been more complicated than we initially anticipated. Equatorial Guinea is very different from Alaska, and so on, so naturally it has taken more time,” Vescovo explains.

“These regions also require different mapping technologies. Shallower than 30 metres, you can use satellites. However, between 30 and 1,000 metres, it becomes challenging – multibeam sonar doesn’t spread very far in shallow water, making it less efficient. But we’re now exploring other approaches for that depth range.”

One of the Ocean Mapper’s most defining features is its role as an inclusive, participatory research vessel. It’s designed to work with local governments, enabling mariners to help map their Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) and territorial waters. This is part of a broader initiative led by Caladan Oceanic, which supports communities in understanding and managing their marine resources free from commercial interests, as the vessel will operate solely on a non-profit research basis.

On this note, I pose the question of what he will actually do with all this data. Do you sell it to governments? Private companies? “There’s no real commercial incentive to give away mapping data,” Vescovo responds. “Oil and gas companies map the seafloor all the time, but it’s proprietary; they don’t share it. Governments do the same for shipping routes. That’s why this kind of data usually only comes from philanthropists or public institutions.”

As part of the continuing effort by my firm Caladan Oceanic to map the seafloor, here is 1,273 square kilometers of Alaskan seashore contributed to Seabed 2030 via SDB for the first time. Thanks to my good partners TCarta and Greenwater Foundation for helping to make it happen. pic.twitter.com/JcAwwWN2rw

— Victor Vescovo (@VictorVescovo) July 28, 2025

According to Vescovo, deep-sea mining, often cited as a concern with ocean mapping, isn’t relevant here either. “The resolution we’re working at isn’t useful for mining,” he says. “The Clarion-Clipperton Zone, for example – it’s already been mapped and characterised in far more detail by the people exploring it for minerals. They know where it all is. Their challenges now are extraction and the business model.”

This isn’t mapping for the sake of mapping, but about sovereignty and safety. In October 2021, the USS Connecticut, a US Navy nuclear-powered fast attack submarine, struck an uncharted seamount in the South China Sea. Not only did it cause an eye-watering estimated $100 million in damage, but it also injured several crew. “These accidents are entirely preventable and they happen because we just don’t know what’s down there,” Vescovo adds. “Even in 2025, some islands in the Pacific still rely on hydrographic charts that date back to early imperial British expeditions. It’s wild that data has just never been updated.”

It’s a noble mission, although it doesn’t end with a single vessel. This is merely what Vescovo hopes is just the beginning, with the Ocean Mapper serving as the foundation for a fleet designed to prove that mapping the entire ocean is as, if not more, realistic than landing on the outer planets.

“Yes, this is a prototype, but I absolutely hope others follow. If more people come on board early, we can lower the price even more by doing multiple builds. It’s always cheaper to build three ships, per unit, than one. But I’m pushing forward no matter what, because in the real world, people usually need to see something to believe it. Even shipyards are now starting to come back and say, ‘This is a great project and we want to be part of it’.”

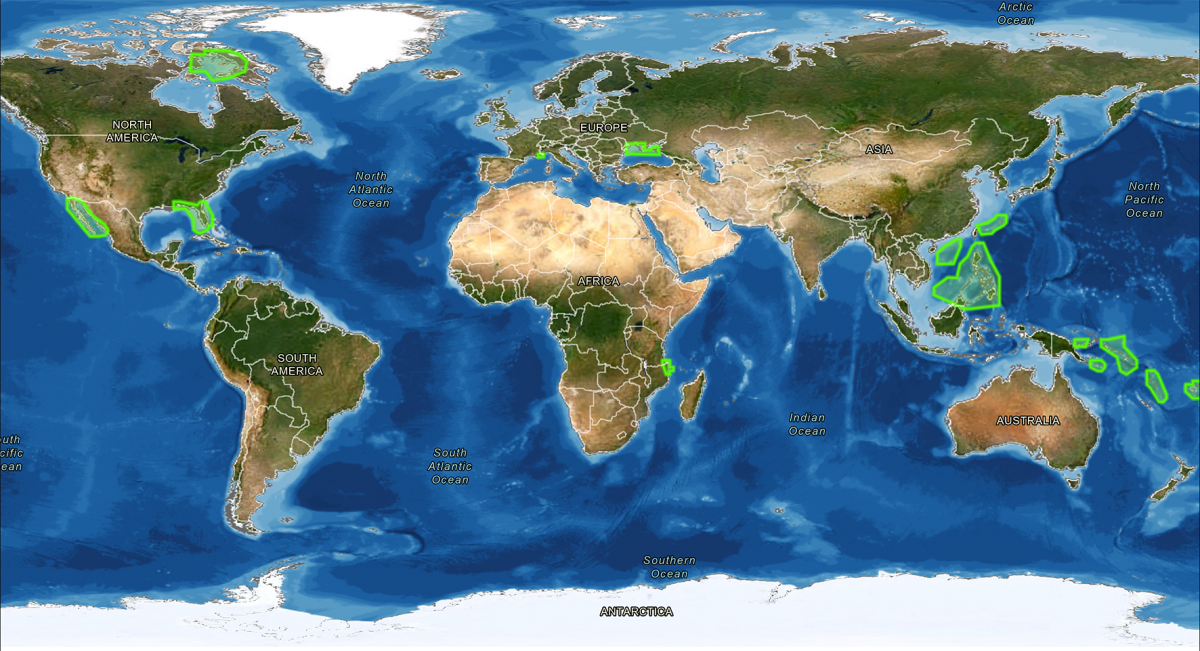

World map of all areas generated

Vescovo remains totally agnostic about who builds it. It is whoever can deliver the quality at the cost they need, and while he says he would love to do it in the States, the capabilities and cost aren’t quite there. Although, ever the intrepid entrepreneur, he discloses that he has invested in another company that’s trying to change that. “It’s not about making it flashy. First, second and third priorities are building the best operating environment for the sonar and getting the data. So now it’s just about getting it built,” he adds.

With that mindset in place, I ask Vescovo what the biggest challenge has been in bringing the project to a shipyard. “Cost,” he says flatly. “That’s the big obstacle. We know we can build it and the regulatory side is manageable as it’s under 23 metres. The technology is proven; the sonar has been running for six years and the hull is optimised. Nothing needs to be invented – it’s just about building it at the right price. For me, the number is around $5 million all-in. That’s the threshold that makes ocean mapping at scale truly viable.”

“Getting people to do the mission, on the other hand? That’s the least of our problems,” Vescovo laughs with a shrug. “We’ve got retired National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) captains, round-the-world sailors, solo yachters. There are two staterooms onboard so that it can accommodate a husband-and-wife team, two friends, or anyone else. It won’t change the cost structure and the appetite is there. People see it’s a good mission and want to be part of something that matters and contribute something meaningful to science and humanity.”

There is something quintessentially human about this innate, unshakable compulsion to explore, plunging beneath the boundaries of knowledge into the unknown. For some, this urge lies dormant, unearthing itself in sporadic flashes of curiosity. For others, it is a gravitational pull, the same force that has launched us to the moon and back in search of answers, advancement and glory – a burning desire to do what no one has done before.

“For a small slice of what you would pay for a chase boat, you would be contributing to the last great exploration on the planet, naming uncharted marine landmarks, etching your name into the earth’s landscape for eternity. That’s the beauty of this mission; it’s understandable. It’s human. It’s history.”

On the surface, ocean mapping might not quite command the space-age spectacle of a silver-screen blockbuster, but it still holds the mythic allure of ancient Atlantis epics. So in 2025, why shouldn’t owners, shipyards and crew embark on a neo-Homeric odyssey of their own?

Rightly or wrongly, yachting has long wrestled with questions of purpose and impact. Some critics point to owners who are unwilling to invest in the broader marine community, clutching their purse strings tightly. But, as Vescovo remarks, there are plenty of ambitious entrepreneurs who could, like Vescovo, become modern-day Explorers Club peers and build one too, if not just for philanthropy, for legacy.

“Sure, there are a lot of vessels out there that are just party boats or convenience vessels. However, if you want to give back to the marine community and a broader society, you can. For a small slice of what you would pay for a chase boat, you would be contributing to the last great exploration on the planet, naming uncharted marine landmarks, etching your name into the earth’s landscape for eternity. That’s the beauty of this mission; it’s understandable. It’s human. It’s history.”

As our conversation winds down, I’m served a cascade of surreal juxtapositions. We discuss his adventures aboard a converted sub-hunter, his passion for restoring classic cars, “de-extincting” the woolly mammoth and plans for mining asteroids. It’s a poignant reminder that time is a shifting truth; what was fact yesterday might be obsolete tomorrow and perhaps the future we imagine is more entwined with our past than we first realise.

Amid the astronomical ambitions, it’s this project that might leave the deepest mark for our community. Legacies carved into coastlines, science gifted to generations, safety charted into being. Maps last longer than memories and history remembers the names written in water. Maybe, just maybe, the final frontier was beneath us all along.

Profile links

NEW: Sign up for SuperyachtNewsweek!

Get the latest weekly news, in-depth reports, intelligence, and strategic insights, delivered directly from The Superyacht Group's editors and market analysts.

Stay at the forefront of the superyacht industry with SuperyachtNewsweek

Click here to become part of The Superyacht Group community, and join us in our mission to make this industry accessible to all, and prosperous for the long-term. We are offering access to the superyacht industry’s most comprehensive and longstanding archive of business-critical information, as well as a comprehensive, real-time superyacht fleet database, for just £10 per month, because we are One Industry with One Mission. Sign up here.

Related news

.jpg)

Explorer yachts – seen from a different perspective

Oscar Siches on how the modern explorer yacht differs from mighty sea creatures like Seawolfe, which carry the weight of history

Fleet

FarSounder joins sea mapping project

The forward-looking sonar technologies manufacturer has partnered with The Nippon Foundation to aid scientific research on the seafloor

Crew

Arksen launches Project Pelagos

The first of the Arksen 85 series has hit the water at the company’s Isle of Wight shipyard ahead of sea trials

Fleet

Analysis: The blindspot

Despite the forward-looking sonar technology coming a long way, uptake has been relatively slow across the broader market

Technology

Related news

A Masterful investment

7 months ago

Explorer yachts – seen from a different perspective

10 months ago

FarSounder joins sea mapping project

2 years ago

Arksen launches Project Pelagos

3 years ago

Analysis: The blindspot

3 years ago

NEW: Sign up for

SuperyachtNewsweek!

Get the latest weekly news, in-depth reports, intelligence, and strategic insights, delivered directly from The Superyacht Group's editors and market analysts.

Stay at the forefront of the superyacht industry with SuperyachtNewsweek