Top stories 2022: Playing with piracy

First published in The Superyacht Operations Report, we examine the working conditions of the men tasked with keeping the fleet safe…

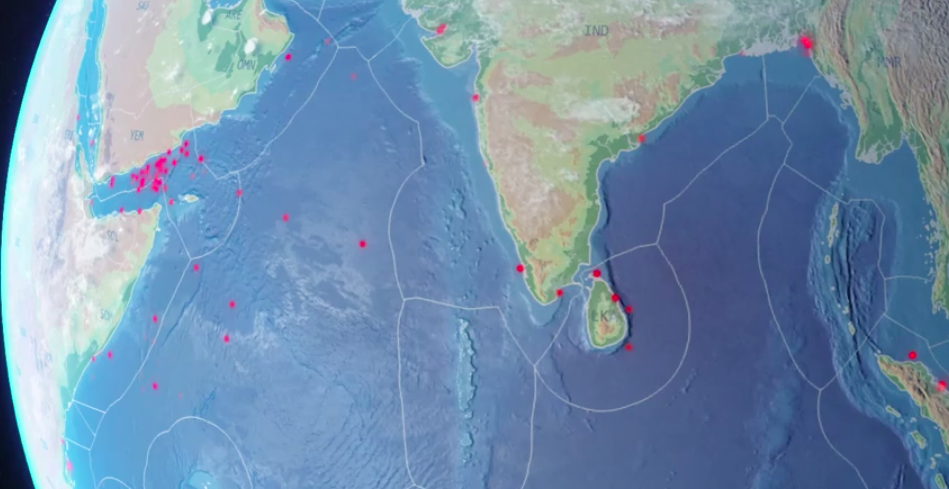

The use of private armed security in the superyacht industry is closely associated with the transit through the Indian Ocean and Red Sea. The so-called Somali Piracy Crisis reached its peak in 2011 when 237 attacks were recorded. The insurance premiums that became associated with moving through the newly defined HRA (High Risk Area) along the coast of Somalia led to a boom in private military security companies (PMSCs) offering protection to commercial and private vessels.

According to the Lowy Institute, by 2012 there were more than 140 PMSCs employing around 2,700 armed contractors. I’ve completed this journey many times in the past 10 years, always with such security on board, and I’ve been both terrified and inspired by my experiences with these teams. Some were professional and conveyed everything one might expect from reading the promotional material from the various websites; others left the crew and myself feeling even less safe than before they arrived.

Reported maritime piracy has since reduced substantially off the coast of Somalia. After the peak in 2011, the number fell to just 14 between 2015 and 2020. This has led to the reduction in the size of the HRA and a general sense that the threat has waned. However, I’ve been on board a yacht that was approached, but this incident was not reported during that time.

I saw a team unable to fire their weapons on approaching skiffs, even when the orders were given. I’ve seen guns jam, weapons assembled incorrectly, rusting ammunition, and listened to men tell stories of the horrible conditions and minimal wages as they lived on floating platforms (converted commercial vessels sitting in international waters) indentured to their next job.

The under-regulated entry to the market of these private security forces, capitalising on the insurance mandates, is an economic reaction to a sudden explosion in demand. Of the dozens of ex-British servicemen who I got to know over the years via the Somali route, Dwayne (not his real name) was the most interesting.

As with most of the men, Dwayne is thickly accented, heavily tattooed, honourably discharged and ultra-fit. Enthusiastic, polite to the nth degree but with an air of menace, he was the embodiment of what I thought security entailed. Dwayne made a few comments during the trip that surprised me. He was visibly furious when our team leader (TL) was nowhere to be seen when approaching the HRA. He was embarrassed and annoyed when the weapons malfunctioned during a live fire test.

However, it was his reaction to the creaks in the system that caught my interest. I reached out to Dwayne recently after he had left the job and, on condition of anonymity, he agreed to share his story. He paints a picture of a broken system and the mistreatment of a vulnerable generation of ex-servicemen.

Hearing Dwayne tell his story went some way to explaining a few of my own experiences. On my first trip, we used a company called Veritas. Although I had no basis for comparison at the time, it’s fair to say that was the high-water mark for the security I’ve worked with since. Apart from over-stating how accurate they were with their rifles during a live fire test, the trip was seamless and the lads made us feel very safe.

Since then, standards appeared to slip as we worked our way through various other providers. One particularly memorable transit occurred as we came through on our way to Sri Lanka. After being coyly informed by the TL that, unlike other trips when we had test-fired the weapons, this time we would not because ‘a properly maintained weapon should never need to be test-fired’.

While in an unofficial convoy about 30 miles from the coast of Somalia, a container ship ahead of us altered course sharply, began firing water cannons and warning shots, explaining – surprisingly calmly on the VHF – that they had sighted five skiffs making an approach and had chased them off.

As we arrived at the same area, all of the security team, myself and most of the crew were enjoying the 4pm excitement on the flybridge. We spotted two skiffs to port … then another three on the starboard bow, all closing ground quickly, painted blue and with groups of men crouching down inside. As they buzzed past it was clear the TL was panicking. By the time the crew started firing flares, the skiffs were turning around and coming back for another pass, so the captain ordered us into the safe room (the engine control room – watertight doors could be locked from either side).

By the time the order to fire came, the scene was a fiasco. The first of the team tried to fire at the skiffs but his rifle jammed. The second helped him to clear it, while the third took aim, calmly tracked the skiff, led it off with his sights and gently squeezed the trigger. At which point the magazine fell out of the rifle, after which we named the dent left by the falling magazine in the BBQ cover after him.

The lads ended up holding their weapons above their heads in a pre-formative show of potential kinetic energy. Fortunately for us, it worked. The secret knock took place and we emerged from the safe room. It was a long 15 minutes, with 10 crew huddled inside, genuinely unsure who was going to come knocking. The sum total of zero bullets had been fired.

This was not reported as a genuine approach, which I still find hard to believe. In subsequent years, I’ve wondered if what I experienced really was a one-off coming together of circumstance or a sign of systemic problems with the training, equipment and preparedness of the team.

Dwayne was furious and apologetic when I told him this story years later on another crossing. He went out of his way to talk to us as a crew, and to reassure us that he and his team would be better if the situation got ‘hot’. I believed him; he had that demeanour that made you feel like it would be OK to follow this man into trouble.

“As well as the training, the standard of the weapons is incredibly poor,” explains Dwayne when we speak. “I remember with you we had issues. I am not sure if you noticed but the gas plugs had been put in incorrectly [gas plugs are a means of regulating the pressure in a gas-operating reload on an automatic or semi-automatic rifle]. If set incorrectly, as we found out, there is insufficient gas redirected from each shot to force the action of the rifle and reload the chamber.

Although I didn’t say at the time, it was hard not to notice the lack of firing during the live fire test. "We don’t expect to have to deal with stuff like that," says Dwayne. "For us it’s simple: “Safety catch, sights, cock the weapon”. We should not be expecting that the weapon has been assembled incorrectly. It’s ridiculous, some of the weapons that we now pick up are honking, covered in rust. They haven’t been serviced properly. Often, they are cleaned but they aren’t serviced.

“These weapons may very well have been sitting in an armoury for three or four months, in the sea salt and air. They are not functional. Some companies will not even instruct a test fire. You have got to ask for it!”

This, I’ve assumed, is why I was swayed from the notion that we would do such a test shortly before our incident. Cost and paperwork. However, Dwayne stresses, “You have got to get rounds away on the superyachts if [for] nothing else [other] than to give the crew the confidence that the weapons work, we know how to use them and when I pull the trigger it’s going to go bang in the general direction of a pirate.”

With the reduced cost, and associated lower pay from some of the providers, has also come lower barriers of entry into the job. As the perceived threat has dropped, so too have the standards. Dwayne explains, “Back in the day, when I was in West Africa, we were on £300-£350 a day. In these regions you are unarmed, you are basically guiding a group of GSF (Ghanaian security forces) or the Togolese navy. You are there to mentor them and instruct them with the weapons, and act as their go-between with the captain.

“Now, I am embarrassed to say this to you, but when we met I was on £104 a day. That is how low it has gotten. The same shipping route was £300 a day in 2012. We are fully armed and heading into a very dangerous region. There are a lot of under-reported close calls, failed attacks that do not get written up. It’s not the most dangerous job I could take, but I’m now expected to run into a barrage of bullets for £104 a day?

“In 2011/12, with the frequency of attacks, the job was obviously paying a lot more. Come 2021/22, it has deteriorated to such a point that some of the operators are using one British TL and then three Sri Lankan or Polish forces. I believe the Albanians are the cheapest, at £25 per day.

“As the British TL with PVI (Protection Vessels International) you are on around £145, with the added responsibility of guiding three other men with poor English, as well as being the main point of contact with the captain. It’s a very difficult situation to manage, and the weight of responsibilities on my shoulders in that situation is ridiculous.”

Recounting another trip, Dwayne says, “This time it was a different company, Allmode [Allmode Yacht Security Service]. I went there with two of these lads and, honestly, I did the test fire of the three weapons because the TL and another bloke didn’t know how to use them. They did not know how to use the weapons correctly.

“It looked a bit like one of them was firing an elephant gun. He wasn’t even looking down the sights. The crew came up to me and said, ‘We are scared’. They said one of the guys on watch would only look through his binoculars when the captain or myself came up to relieve him. I spent the crossing sleeping closer to the bridge so I could react in time if they needed me.

“Honestly, it’s just a cost device with some of the cheaper operators. There are some companies that I have worked with, like Veritas, Citadel, EOS Risk, to whom things like test firings and weapons checks are paramount. They insist on the team carrying out a firing and demonstration. Others, to save money, place it as an optional extra for the boat.”

While my experience with the weapons is limited, having Dwayne explain the reasons why things appeared to go so wrong on some of my trips was eye-opening. The difference between the initial trip with the admittedly more expensive team from Veritas was very different from what I experienced with Dwayne and some of the cheaper operators such as PVI. The route was the same and, therefore, the service should be also.

Crucially, the experience of the men tasked with our protection must be re-examined. I asked Dwayne if he thought some of the companies were targeting men out of the service in a way that he felt was misleading. “Absolutely. These lads have got to find an income,” says Dwayne. “They have to find money for mortgages and the bills. It’s a hard transition for many of them to go from a job that provides three square meals a day and keeps you housed. So many of them jump on a job like this and next thing it’s been 10 years, and they’ve only been doing it because it’s the only job they think they are capable of.

“They have that soldier mentality and that is how they perceive themselves. It’s hard to adapt to civilian life so they will stick at a job like this, despite the conditions. That is certainly how it was for me. You’re kind of fulfilled, but you don’t know where else to turn. You’ve not being given [other] skills and attributes [apart] from what you’ve been taught in the corps, which is obviously to run towards bullets and to kill people.

“The cost saving has affected the living conditions for the lads terribly. Guys are spending weeks with shocking food, horrible sanitation and over-crowded accommodation. All of this means that by the time a job comes around, literally any job, they will take it because they are malnourished and desperate to leave.”

Dwayne has shared a shocking video taken from inside one of these vessels, where the teams live between transits. There is sewage in the hallways, inedible food and no amenities for weeks at a time. I had no idea that conditions were like this, but I recall once, when dropping the team off, they asked if there was any way we could spare them some food. Being unsure if they were angling for some of the expensive luxury provisions they assumed we had, we asked them to clarify. They said simply, ‘Have you got any fruit or vegetables as we have nothing on board?’. I’ve never seen a group of guys so appreciative of a bag of oranges and apples.

Some operators will fly personnel into the Seychelles or the Maldives on a job-by-job basis, with an associated higher cost. Others, such as PVI and Ambrey Risk, make use of these offshore platforms. Dwayne was at pains to say that many of his friends had left because of the appalling conditions that he described and showed, and also that many of them should not have been there in the first place.

When the threat was at its most apparent, the bar for entry was high. Age restrictions and minimum service requirements equated to much higher standards and wages. As the unregulated market worked over the system, some of these providers are now not doing the job or providing the service that they advertise.

If piracy, as it manifested off the Somali coast, can be seen as a reaction to societal pressures, then it’s likely that we’ll see it re-emerge globally. West Africa remains volatile for shipping, the Straits of Malacca and the Amazon also. Millions are likely to be displaced in the coming decades due to climate change and the decimation of the world’s fishing grounds.

As superyachts – the shining symbols of capitalist over-indulgence – travel further, they will be targeted. If we are to continue to use private security personnel from under-regulated companies, they need to be treated, trained and equipped better than I saw and what Dwayne has recounted.

These men and crew are in harm’s way, and while the specific risk from the Somali Crisis that drove the issue into the public eye may be reduced, it has not disappeared. Undoubtedly, the system of PMSCs will continue to be called upon both in the Indian Ocean and further afield.

Superyacht managers, financial controllers and captains should question why a particular operator is the cheapest. Ask what conditions the men are subjected to, how much they will be paid and where they will be based between jobs. The market forces have driven the standards in parts of the industry below a safe level. Without clear regulations, the responsibility may be on us as an industry to ask the questions and demand better. We should look beyond insurance cost calculations. The crew should be safe and these lads deserve better.

Image credit; Nelson Shufer 2021 - Piracy attacks reported in the Indian Ocean

NEW: Sign up for SuperyachtNewsweek!

Get the latest weekly news, in-depth reports, intelligence, and strategic insights, delivered directly from The Superyacht Group's editors and market analysts.

Stay at the forefront of the superyacht industry with SuperyachtNewsweek

Click here to become part of The Superyacht Group community, and join us in our mission to make this industry accessible to all, and prosperous for the long-term. We are offering access to the superyacht industry’s most comprehensive and longstanding archive of business-critical information, as well as a comprehensive, real-time superyacht fleet database, for just £10 per month, because we are One Industry with One Mission. Sign up here.

Related news

Democratising drone defence

We speak with Richard Gill, CEO of Drone Defence, about trickle down economics and educating the market

Technology

Beazley launches cyber policy to strengthen superyacht defences

Risk management has played a key role in the creation of affirmative cyber insurance

Technology

ISPS: security and new deal in yacht management

Floating Life captains’ meeting informs attendees of preventative safety measures required on board

Crew

Related news

Democratising drone defence

4 years ago

ISPS: security and new deal in yacht management

6 years ago

NEW: Sign up for

SuperyachtNewsweek!

Get the latest weekly news, in-depth reports, intelligence, and strategic insights, delivered directly from The Superyacht Group's editors and market analysts.

Stay at the forefront of the superyacht industry with SuperyachtNewsweek