Unlocking the hidden potential of the legacy superyacht fleet

Simon Brealey at Lateral Naval Architects on how owners can modernise their yachts to align with contemporary environmental and technical standards…

At the 2025 Superyacht Forum, the subject of sustainable refits once again rose to the top of the agenda. This was hardly surpising. With more than 3,000 superyachts currently in operation worldwide, most of them delivered within the last 30 to 35 years, the industry finds itself confronting an unavoidable reality: much of the global fleet was designed and built in an era when sustainability, energy efficiency and lifecycle emissions were peripheral concerns at best.

In contrast, today these topics sit at the very centre of discussions around responsible ownership, regulatory risk and the long-term viability of yachting itself. For many stakeholders, sustain-ability is no longer a question of incremental improvement but an existential issue for the sector. Against this back-drop, a seemingly obvious question emerges: should owners not be modern-ising their existing yachts to align with contemporary environmental and technical standards?

From an engineering perspective, the answer is both encouraging and complex. Through the growing body of work undertaken on legacy yacht refits, one conclusion is clear: most older yachts possess enormous, untapped potential for improvement. The challenge lies not in whether this potential exists, but in how best to unlock it in a way that is technically sound, operationally sensible and aligned with owner ambition.

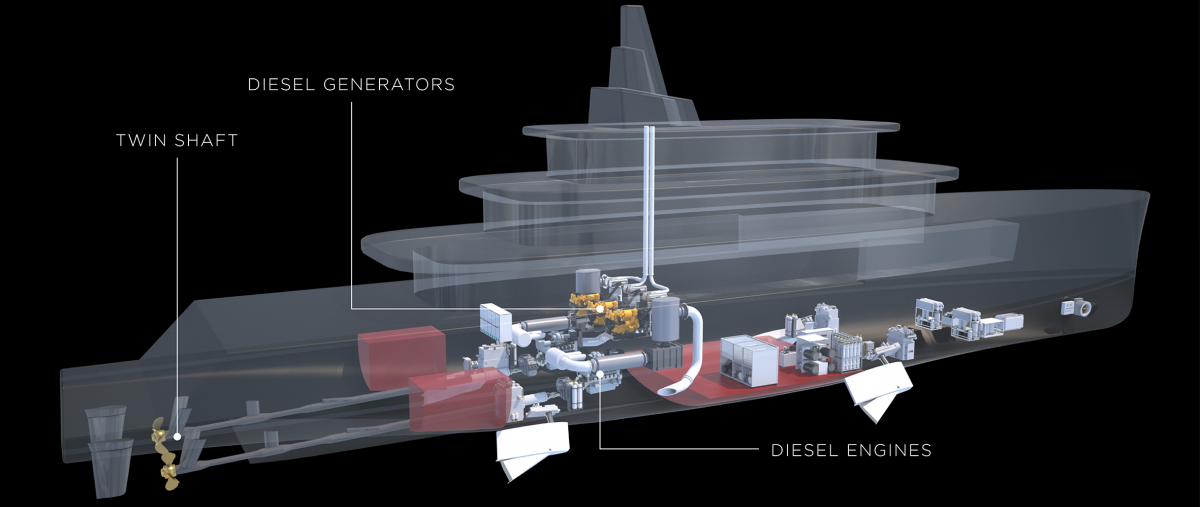

First-hand experience over the last 20 years illustrates how and why legacy yachts differ so markedly from their modern counterparts. The early 2000s marked a period of explosive growth in large-yacht construction. Design priorities during this era were shaped by a particular set of market drivers: headline speed figures of 18 to 22 knots, large direct-drive diesel engines and hull forms optimised for performing at maximum speed. Superstructures were often bulky, with design features aimed at maximising interior volume and usable square metres per gross ton or metre of length.

Most older yachts possess enormous, untapped potential for improvement. The challenge lies not in whether this potential exists, but in how best to unlock it in a way that is technically sound, operationally sensible and aligned with owner ambition.

These yachts delivered extraordinary levels of luxury and comfort, and they remain impressive platforms today. But the simple fact is that very few of them operate anywhere near their top speed at any other time than the original sea trial. Because they are often optimised around use of space rather than efficiency the penalty for this speed is very high, many of them carry large machinery around for no good reason. In this era there was no priority given in the design for real-life operations and factors such as fuel efficiency, emissions and energy management.

Over the past decade, the industry has undergone a quiet but profound shift. New-build yachts are increasingly designed around how they are used rather than how they might be marketed. Comfort, efficiency, reliability and range now dominate design briefs, normally with lower speeds specified that suit real-life operations. This evolution has been driven partly by changing owner expectations and also by the maturation of enabling technologies such as electric propulsion, energy storage and data-driven tools. The result is a widening gap between the design philosophy of modern yachts and that of the legacy fleet, a gap that represents a significant opportunity for refit-led modernisation.

When sustainability is raised in the context of refits, often the discussion can quickly become unfocused. Owners and their teams are often confronted with a bewildering array of technologies and competing priorities. It is important to take a systematic approach based on available data and a strong understanding of the owner’s overall aims and ambitions. A refit study that begins with a fundamental analysis of how energy is generated, distributed and consumed on board is key, together with a structured approach to analysing design improvements.

It’s key to understand the limits and expectations surrounding the cost and accepted time out of service, balanced against the owner’s desire for innovation and tolerance of risk and failure.

These improvements should also consider that sustainable refits rarely revolve around a single intervention. Instead, they sit at the intersection of multiple objectives: ongoing preservation of the yacht, improving reliability, addressing equipment obsolescence, enhancing on-board comfort and providing more operational capability.

The risk profile and ambition of the owner is also vital in identifying solutions which meet these objectives. It’s key to understand the limits and expectations surrounding the cost and accepted time out of service, balanced against the owner’s desire for innovation and tolerance of risk and failure.

Some owners are curious about the latent potential within an asset they already value highly. Others are new custodians, eager to put a personal stamp on their yacht or to rectify perceived shortcomings. Some are driven by environmental values, others by operational frustrations, reputational considerations or future resale value.

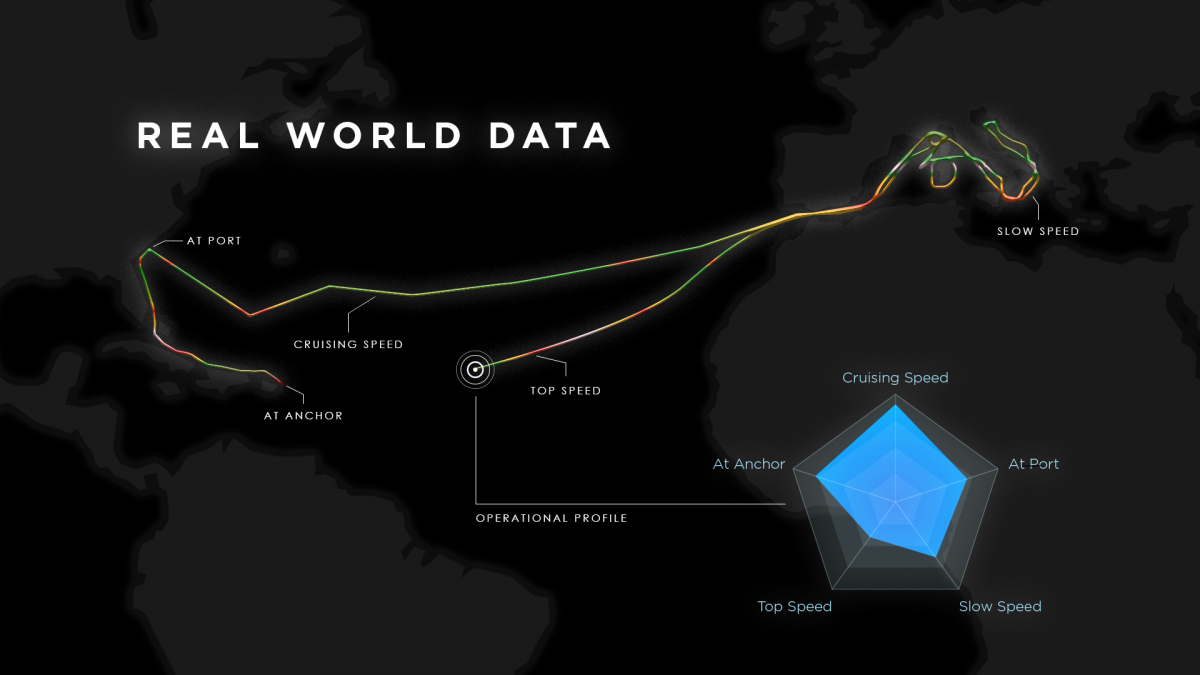

One of the most important lessons learned from sustainable refit studies is that there is no universal solution. Yachts of a similar design can also require different solutions depending on how and where they are operated. Is the yacht a globe trotter, covering high mileages and operating in diverse areas of the planet’s oceans? Or does the yacht operate a single season in the Mediterranean? Is the yacht’s power generation optimised? How fast does the yacht cruise? What impact does the crew have on energy consumption on board? These factors will all present different opportunities.

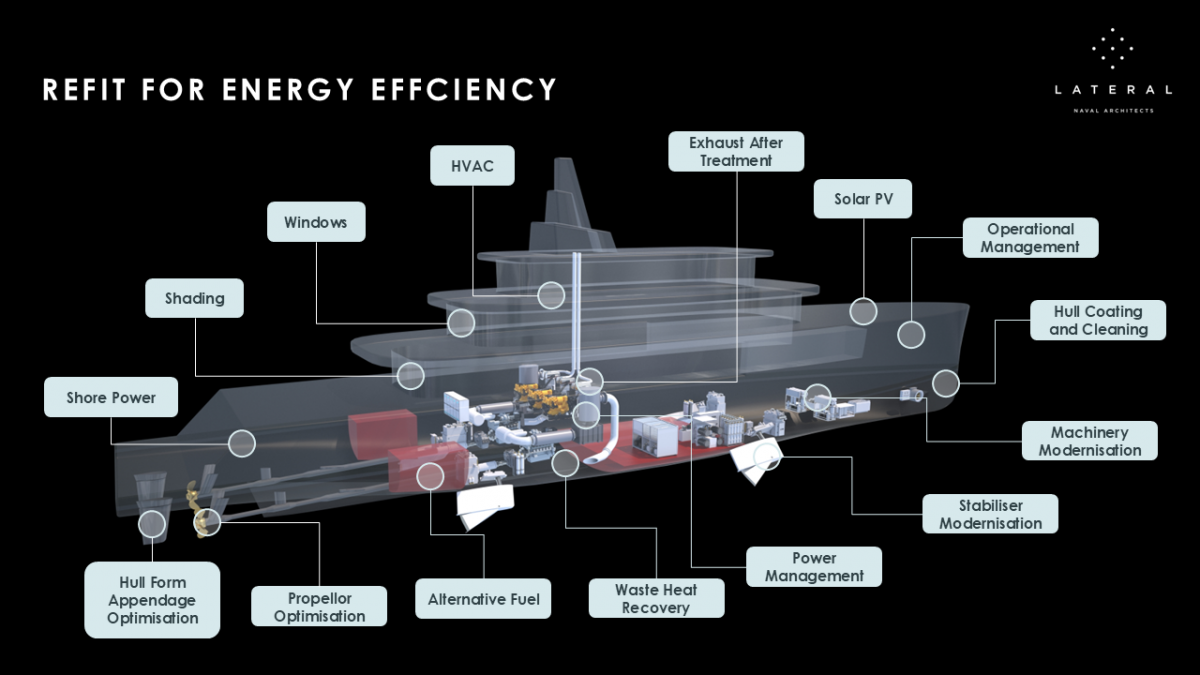

Areas of a yacht suitable for refit to improve engine efficiency.

Before any meaningful engineering decisions can be made, the yacht itself must be understood not only in how it was designed and specified but also how it is operated today.

It’s highly likely that the yacht will have changed hands and/or the original management team or crew which worked on the project’s build will have departed, so it is an important task to decode the original design intention of the yacht. A large amount of insight can be extracted from original documentation: general arrangements, machinery layouts, system diagrams, stability booklets and electrical load balances. Reverse-engineering these drawings using the experience of a new-build process often reveals mismatches between original assumptions and current reality.

The current reality can often be difficult to distil accurately with a wide discrepancy of data and understanding within the fleet. Crew interviews, voyage itineraries, engine logs, maintenance records and operational anecdotes all add valuable context.

Given the scale of opportunity, one might expect sustainable refits to be far more common than they are. However, uptake remains limited. The primary reason is not technical feasibility, but the absence of compelling external drivers.

Increasingly, big data also plays a central role. Automatic Identification System (AIS) data, when combined with weather and oceanographic datasets, allows a reconstruction of how a yacht moves through the world. By processing this data, it becomes possible to create a virtual operational profile: typical speeds, time spent at anchor, generator loading patterns and environmental conditions encountered. This can be enlightening to a crew, management team or owner. It allows guess work to be reduced. Simply put, to improve, one must first measure.

This data allows a basic digital twin of the yacht to be modelled. Using developed knowledge, in-house databases and project specific calculations the impact of changes can be estimated. This allows changes to be simply illustrated as either reduced energy consumption, improved comfort, reduced fuel usage in real percentage terms and reduced greenhouse-gas emissions.

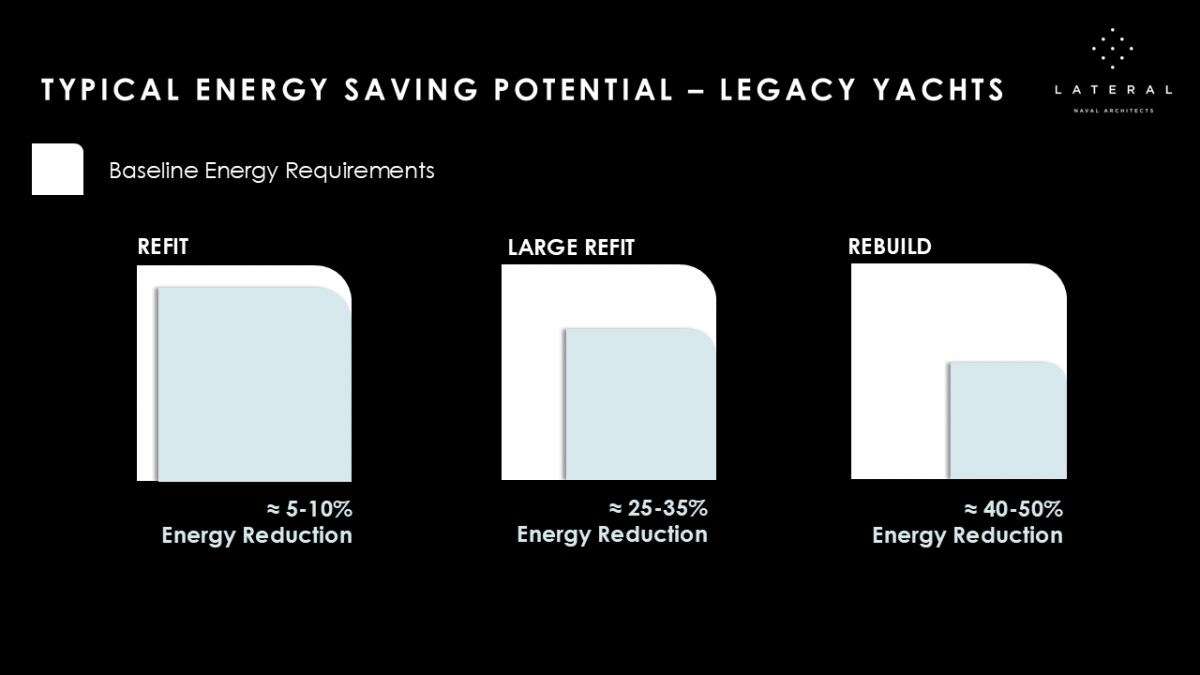

A representation of the energy savings possible with various degrees of ‘refit’.

Data-driven analysis often produces surprising results. For some owners, the absolute scale of energy consumption is eye-opening and somewhat sobering. For others, it can challenge perceptions. Sometimes it becomes apparent that despite modest cruising speeds, propulsion energy use is comparable to or even higher than the hotel load required to support on-board systems. This revelation can be useful to understand why changes to the propulsion efficiency of the yacht may be just as valuable as changes to the hotel load.

These insights help identify the so-called low-hanging fruit: interventions that deliver disproportionate benefits for relatively modest effort. They can also highlight operational practices that, if adjusted, yield immediate gains. As an example, correlating fuel consumption with time since the last cleaning of the hull normally provides compelling evidence of the value of proactive hull maintenance.

In many cases, a combination of minor technical upgrades and operational refinements can reduce total energy consumption by 5 to 10 per cent. Measures in this category include: properly sized and utilised shore power connections – while most of the fleet now operate on low-carbon efficient grid energy in marinas where it is available, some yachts may need upgrades to allow them to operate effectively (or at all). Full conversion to LED lighting is very normal for most yachts, adopting it will reduce electricity and get further gains from reduced air conditioning demands. The introduction of variable-frequency drives on pumps and fans, especially those which continuously operate, can ensure that power demand is drastically reduced. Replacement of outdated domestic appliances to newer more efficient models reduce electricity, heating, and water requirements. Operational optimisation of loading conditions, route planning and maintenance combine to provide quick benefits.

While there are many ways to measure the effectiveness of a sustainable refit, energy efficiency is the best metric. By using less energy many of the other important factors will follow. Using less energy should be a clear, sensible goal for all refits.

Although these improvements are worthwhile, many yachts have already implemented some or all of them. To achieve more substantial gains in energy, more ambitious interventions are required.

While there are many ways to measure the effectiveness of a sustainable refit, such as fuel consumption or greenhouse-gas emissions, energy efficiency is the best metric. By using less energy many of the other important factors will follow. Using less energy should be a clear, sensible goal for all refits.

This would apply even if the yacht were considering switching to a drop-in renewable fuel option, such as hydrogenated vegetable oil (HVO). HVO can offer an immediate reduction in lifecycle carbon emissions of up to 90 per cent, a significant solution for legacy yachts concerned with environmental impact. However, avail-ability constraints and cost premiums relative to marine diesel mean that energy efficiency becomes even more critical when using HVO, maximising the environmental benefit per litre consumed.

Moreover, questions around long-term HVO feedstock supply and competition for that feedstock suggest it may need to be considered as an interim solution. This reinforces the importance of reducing overall energy demand first, thereby limiting fuel consumption and emissions regardless of fuel type.

The image indicates a typical legacy yacht installation using diesel direct-drive engines.

The image depicts a typical layout for a state-of-the-art new-build yacht with electric propulsion and capable of dual diesel/methanol operation.

When refits are aligned with larger yard periods, the scope for meaningful improvement expands significantly. At this level, opportunities emerge across multiple systems:

• Advanced antifouling coatings can reduce resistance and simplify cleaning. The appendages on the hull will very probably have been originally designed for speeds the yacht now never operates at. Adjusting them will improve efficiency for actual operating speeds.

• Re-optimised propellers designed for realistic cruising profiles can deliver propulsion efficiency gains, resulting in less power usage.

• Basic waste-heat-recovery systems can heat or preheat domestic hot water using heat rejected by the engine, reducing electrical energy consumption and generator load.

• Replacing obsolete engines or generators can address spares availability, improve emissions compliance and lower fuel consumption.

• While modest in absolute terms, ambitious solar photo voltaic instal-lations can still make a meaningful contribution when integrated into a broader energy strategy. With a good data-driven understanding of how and where the yacht operates, this benefit can be easily quantified.

• Modern battery systems can correct generator mismatches or errors in the initial electrical load estimate.

This can potentially reduce generator low-load operation where perhaps multiple generators operate. Avoiding low load running can reduce the individual running hours of generators thereby extending maintenance overhaul time-scales. Operating generators in an optimum load setting can also improve reliability, efficiency and reduce exhaust emissions.

Using the data to map a yacht’s operational profile can help to drive choices in refit.

• Upgrades to chillers and chilled water systems often yield some of the largest efficiency improvements available due to the constant high energy consumption of these systems.

• During a refit it may be possible to incorporate increased exterior shading into other planned design changes which can dramatically reduce cooling loads and subsequent energy demands of the air-conditioning system.

• The stabilisers can be upgraded to use the latest high-efficiency hybrid hydraulic power packs or replaced entirely with electric stabilisers. These upgrades reduce energy consumption while also providing an opportunity to correct any suboptimal seakeeping behaviour and enhance on-board comfort.

Taken together, these measures can typically reduce a yacht’s overall energy consumption by 25 to 35 per cent.

Beyond this lies a more radical category of intervention, where the line between refit and rebuild becomes blurred. These projects involve longer downtime and greater investment, but they unlock transformative potential.Advanced HVAC architectures, improved glazing with superior thermal performance, comprehensive high-capacity waste heat recovery systems, hybrid electric propulsion systems and hull lengthening can all be considered. Alternative fuels and power systems can also be considered. While regulatory and technical challenges remain significant, and commercial risks are high, options such as methanol reforming fuel cells may represent the ultimate upgrade for a small number of innovation-focused owners.

When combined holistically, such measures have the potential to reduce energy consumption by up to 50 per cent, fundamentally altering the operational footprint of a legacy yacht.

For sustainable refits to gain momentum, the wider yachting ecosystem must evolve. Shipyards, naval architects, engineers, yacht managers and crew all have a role to play in reframing the narrative.

Given the scale of opportunity, one might expect sustainable refits to be far more common than they are. However, uptake remains limited. The primary reason is not technical feasibility, but the absence of compelling external drivers. Regulatory pressure remains weak and even emerging environmental frameworks are unlikely to provide enough of a clear return on investment for refit-based sustainability measures. Without clear environmental regulations most owners, quite understandably, struggle to justify the cost and inconvenience of extensive upgrades.

There is also a psychological divide between new builds and refits. New construction is associated with excitement, innovation and vision. There remains a small core of visionary new-build owners who have and are creating iconic yachts by taking risks and making emotional decisions. Refits, particularly technical ones, are often perceived as expensive necessities rather than opportunities. An engine overhaul rarely inspires the same enthusiasm as a new concept on a blank sheet of paper.

For sustainable refits to gain momentum, the wider yachting eco-system must evolve. Shipyards, naval architects, engineers, yacht managers and crew all have a role to play in reframing the narrative. We need to present refits not as compromises but as opportunities to rediscover and reinvent valued assets, to restore classics to their former glory. For owners that have technical interests and a spark of curiosity, we must ensure that we can provide them with the correct information and data to fuel their fire.

This requires trust, creativity and a willingness to challenge conventional thinking. While some ideas may initially seem unconventional now, the reality is that the fleet will continue to age while technology advances relentlessly. In time, restoring and rebuilding a yacht may become less of an emotional decision and more of a rational decision based on avoiding obsolescence and unlocking opportunity.

This article first appeared in The Superyacht Report: Refit Focus. With our open-source policy, it is available to all by following this link, so read and download the latest issue and any of our previous issues in our library.

Profile links

NEW: Sign up for SuperyachtNewsweek!

Get the latest weekly news, in-depth reports, intelligence, and strategic insights, delivered directly from The Superyacht Group's editors and market analysts.

Stay at the forefront of the superyacht industry with SuperyachtNewsweek

Click here to become part of The Superyacht Group community, and join us in our mission to make this industry accessible to all, and prosperous for the long-term. We are offering access to the superyacht industry’s most comprehensive and longstanding archive of business-critical information, as well as a comprehensive, real-time superyacht fleet database, for just £10 per month, because we are One Industry with One Mission. Sign up here.

Related news

The Superyacht Report 227: Refit Focus – out now!

From people and paint capacity, to project control and insurance, we asked the refit market what really matters to them. Read TSR: Refit Focus today…

Crew

Yachting deliberately

Aino Grapin sets out how she believes the industry is on the cusp of change in embracing sustainability, where shipyards and visionary owners can work together

Fleet

Royal Huisman to trial improved wing sail and fuel cell systems

The Dutch shipyard’s new concept aims to bridge experimental clean-energy tech and real-world yacht design with a 50-metre wing-sail catamaran

Fleet

Pressure to adopt biofuels mounts as regulation bites

Lloyd’s Register’s latest Fuel for Thought report positions HVO as the most practical near-term alternative to conventional marine fuels

Crew

Teak decks, wood options and sustainability in yacht decking

An interview with André Hofmann, head of marketing & sales series yachts at Wolz Nautic, on the current situation in the teak market and plantat

Fleet

Related news

The Superyacht Report 227: Refit Focus – out now!

2 months ago

Yachting deliberately

5 months ago

NEW: Sign up for

SuperyachtNewsweek!

Get the latest weekly news, in-depth reports, intelligence, and strategic insights, delivered directly from The Superyacht Group's editors and market analysts.

Stay at the forefront of the superyacht industry with SuperyachtNewsweek